What Does Likes Mean On Facebook

When Facebook first unveiled News Feed in 2006, its 10 million users threatened to revolt. In a matter of months, though, the redesigned product took off with users and, ultimately, advertisers. The familiar, blue-bordered scroll of news articles and baby pictures now reaches 2 billion people around the world and accounts for much of the company's more than $30 billion in annual advertising revenue.

But in 2017, News Feed is more controversial than ever, under fire for reinforcing partisan viewpoints by creating social echo chambers, spreading misinformation, and, through its targeted advertising tools, possibly enabling election interference. As investigations unfold into how Russian intelligence operations manipulated Facebook, it's clear that News Feed has become a political weapon capable of striking painfully close to home—and some users are rethinking its place in their lives.

The controversy exacerbates a more basic business problem for News Feed: Revenue growth has been falling every quarter for the past year, and Facebook executives have suggested to investors that News Feed capacity is, in part, the culprit. With ads already littering users' feeds, there is dwindling real estate available for additional ones, and the quality of the experience is starting to suffer.

Amid this complex maelstrom of controversy and stuttering growth, Facebook has been increasingly turning its attention to another form of social interaction: messaging. Last year, for the first time, the world's largest messaging platforms surpassed the world's largest social networks in terms of monthly active users. Messenger, Facebook's satellite app for private conversations, has 1.3 billion monthly users; WhatsApp, which Facebook acquired for $22 billion in 2014, has 1.3 billion monthly users of its own. Whether these platforms are the next big revenue spigot—or the next frontier of exploitation—may be one of the biggest questions facing Facebook's future.

So far, both Messenger and WhatsApp are largely unmonetized—a fact that seemed to irk CEO Mark Zuckerberg on a recent earnings call, when he mentioned wanting to "move a little faster" in bringing more ads to chat. The comment set off a flurry of investor speculation: Wall Street knows that if Zuckerberg and his team can turn one or both of their enviable messaging assets into revenue generators on par with News Feed, the windfall would be enormous. (WeChat, the messaging app run by China's Tencent, elevated the parent company's annual ad revenue from zero to $4 billion in the span of just two years.) The question is whether Facebook can introduce brands into chat—and then turn on the revenue tap—without sabotaging the implied intimacy of messaging, or following News Feed into a credibility crisis.

The task of solving that delicate puzzle has fallen to David Marcus, Facebook's vice president of messaging products. A dignified but unassuming presence at Messenger's Menlo Park headquarters who favors faded jeans and speaks with the slight accent of a native Parisian, Marcus has helped Messenger add 1 billion monthly active users since he left PayPal to join Facebook in 2014.

Before Marcus took over, Messenger's positioning in the market was unclear. Between Gchat, iMessage, Skype, and Snapchat, there was no shortage of options for private digital conversations. Marcus quickly concluded that Messenger needed more compelling features to draw in users. In the past few years, he has helped introduce augmented reality, group video chat, video-chat filters and masks, stickers, social games, and more to lure in Facebook users with media-rich ways to chat that are particularly attractive to groups of people.

"By offering richer tools for people to communicate, we've managed to make it more and more of a primary messaging platform," he says. "When you're not the incumbent, you need to differentiate."

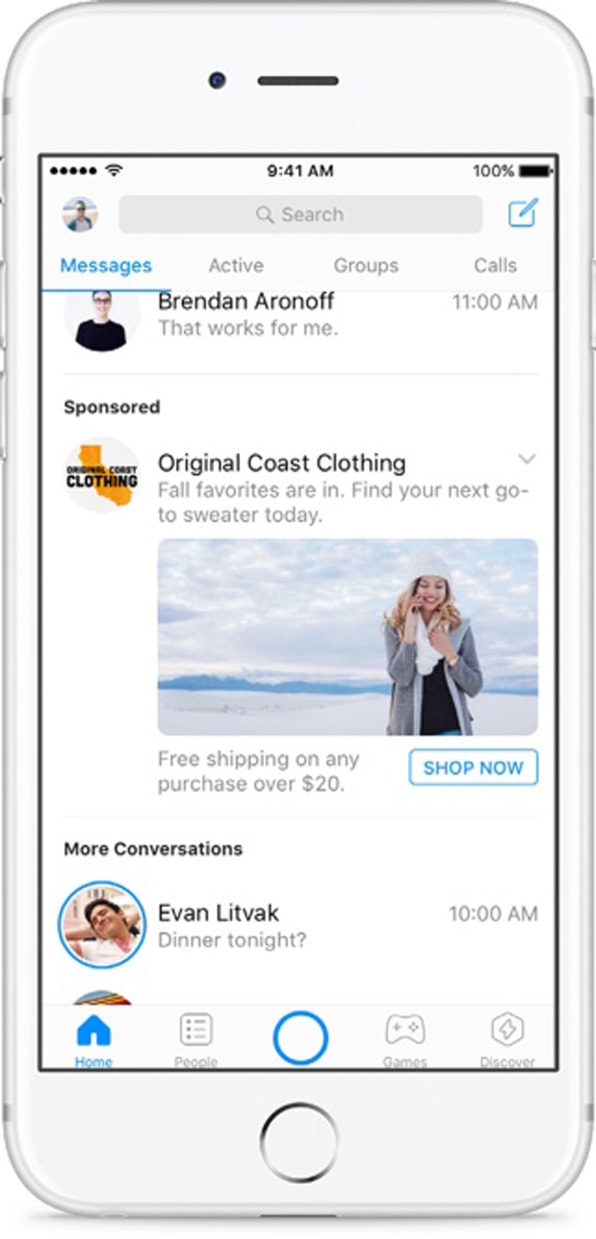

Marcus has also had to be creative in introducing ad products to the platform. In recent months, his team has launched Click to Messenger ads, which take users from a News Feed or Instagram post to a conversation with a brand in Messenger; Messenger Inbox ads, which appear alongside open threads with friends and family; and Sponsored Messages, a retargeting product that allows advertisers that have previously conducted a conversation with a user to reengage. The goal is to get people communicating directly with brands and small businesses from within the Facebook ecosystem. After all, why open a browser tab to search for a business and then call a phone number (that no one answers) when the process can be condensed within Messenger?

"Businesses want to open more conversations with potential customers or existing customers," Marcus says. He predicts that, before long, "people will have a habit of coming to Messenger for every business interaction," from haircut scheduling to UPS tracking, because the experience will be far superior to that of 1-800 numbers, email order confirmations, and Twitter.

Much of Marcus's vision relies on chatbots, which can automate replies within Messenger. Brand interactions, in a messaging context, perform better when they are personalized—taking into account, for example, a user's order history or color preferences. Brands also have to insinuate themselves into a very intimate environment, full of exchanges with friends and family, at exactly the right time. A few years ago, it would have been prohibitively expensive for marketers to individualize their interactions this way. But thanks to AI, an area in which Facebook has invested heavily, chatbots are now getting better at personalizing on a mass scale.

Meanwhile, Messenger is getting a boost from Facebook's 70 million active businesses. In a matter of months, tens of thousands have appeared on the chat platform. Users can chat with Kim Kardashian's bot about her weekend plans, buy movie tickets via Fandango, and book a Mercedes test drive. There are even some Messenger-only businesses: SnapTravel, for example, uses bots and human travel agents to book hotels via chat.

The majority of these business accounts are still manned by real people, who respond asynchronously. But Messenger is encouraging brands to create automated experiences, despite the fact that many still come across as a bit, well, stupid. A Trulia bot, for example, didn't understand my interest in renting an apartment in a Brooklyn brownstone, something that would take just a few clicks on a website like StreetEasy. An Adidas bot, designed to showcase the brand's fitness studio, was stumped by my simple "buy shoes" query.

Yet Messenger bots are doing one thing remarkably well: With every interaction, they are collecting data and developing profiles of users. Although Facebook is still a long way from bringing the AI it has developed for News Feed ad targeting to Messenger's conversational context, Marcus is laying the foundation. In July, at a daylong event designed to showcase and gather feedback from a dozen of the 100,000 developers that are now active on Messenger, he updated attendees on Messenger's latest AI capabilities, designed to help bots better understand unstructured user questions.

"A big requirement to automation is understanding what people are asking," he said. So Facebook was making its natural-language-processing knowledge available to developers. "It's a little geeky, but it actually will enable automation at scale."

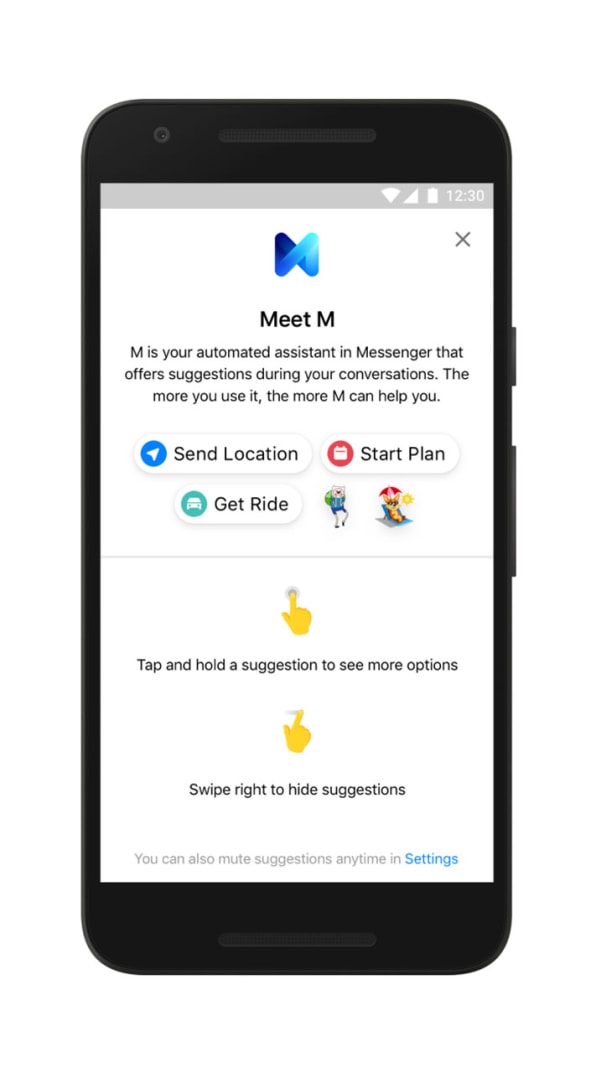

Deploying conversational data doesn't just help developers create business bots for brands; it also gives Messenger an edge with its own virtual assistant, dubbed "M." Earlier this year, the assistant started inserting third-party bot suggestions into private conversations, as a way to encourage people to interact with them. If users are receptive, M could become a powerful way to start building business-to-consumer chat across the Messenger user base, says Kemal El Moujahid, director of product management for Messenger Platform and M.

The ultimate vision is to create an all-encompassing ecosystem along the lines of WeChat, which serves as a gateway to chat, news, shopping, and more for a billion Chinese consumers. "The whole thesis is, users are going to be able to run their life from Messenger," El Moujahid says. "[Users] want to be able to play a song, book a restaurant, all within Messenger. So by making it very efficient for businesses to deliver these services in a frictionless way, then we're really serving our users." Adding the ability to transact would be a natural extension.

Related: How WeChat Became China's App For Everything

Might the public backlash Facebook is facing and potential regulatory changes complicate Messenger's grand plans? Without question. In the midst of the Russian ad investigation—which has now extended to how Russian agents used Messenger to communicate with users—Facebook is enhancing the way it discloses political advertisements (and all ads, period) and creating a searchable archive of federal-election related ads. That solution is much more unwieldy on Messenger, where ads take the form of one-on-one conversations. "It's one thing to be selling a product at the exact right time," says Robyn Caplan, a researcher at the Data & Society think tank, of Facebook's ad targeting. "It's another thing to start selling ideas at the exact right time. What are the circumstances in which [targeting] should be allowed? We've created specific guidelines around ads in past media regimes."

And then there's the question of how company might identify—or intercept—propaganda and bad actors in the intimate context of Messenger, which could be near-impossible.

On the one hand, if successful, Messenger is creating a personalization machine, powered by Facebook's enormous data sets, that could help the messaging service move well ahead of its competitors. (Imagine, for example, a version of M that morphs from text-based chat to vocal assistant on a Facebook-designed home device—and leaves Alexa in the dust.) But the rise of Messenger ad tech also raises the dark specter of content so individually specific that it could change user behavior in the voting booth or even incite users to real-world violence.

Sound far-fetched? These disturbing scenarios have already played out in real life, catalyzed by the other messaging service Facebook owns: WhatsApp.

For years, Facebook has asked users to hand over personal data in return for social utility. With Messenger, Facebook is offering them commercial utility as well. But for people who are already wondering if News Feed has become too influential, the price to pay may be simply too high.

This story has been updated to reflect Facebook's new political ad disclosure rules.

What Does Likes Mean On Facebook

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/40490938/what-does-facebook-messenger-mean-for-the-future-of-political-propaganda

Posted by: drinnonhused1980.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Does Likes Mean On Facebook"

Post a Comment